Jesus Christ and the Holy Grail.

Et accipiens calicem, gratias egit: et dedit illis, dicens: Bibite ex hoc omnes!

Since the crucifixion of Jesus Christ (7 April 30 AD), the cup which Christ offered the twelve disciples at the Passover meal known to history as the Last Supper, became the most sought-after religious relic in history (Matthew 26: 27, Mark 14: 23; Luke 22: 17).

This sacred chalice has long been shrouded in enigma, as variously venerated by storytellers as it has been ignored by more orthodox Christian theologians. Never the less, a mass of mainly literary evidence has survived, which mixes myth and post-evangelical narratives in equal measure. Among the most talented literary authors who latched on to the tale in the medieval period was Chrétien de Troyes, who in turn was inspired by Celtic-Breton and probably Occitan troubadour authors, though the Occitan influence has not been studied in depth. The 9,234 rhyming octosyllables of his masterpiece Perceval, le Conte du Graal introduces us to chivalric literature through a plot located in the semi-mythical world of King Arthur, who sends out his knights in search of the Grail containing the blood of the crucified Christ. Curiously, Chrétien died before finishing the work, thus inspiring many continuators of his story.

It was Robert de Boron in the early thirteenth century who established the relationship between the Grail, the cup used at the Last Supper and Joseph of Arimathea. According to this account, the resurrected Jesus appeared to Joseph of Arimathea to entrust him with the Grail, and ordering him to take it to the island of Britain.

Contemporaneously, Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival (undoubtedly the finest medieval work ever written on the myth) associated the Grail with an unlimited source of power from which wealth and abundance emanates through the paradisiacal conduit of divine perfection.

A late medieval typographical error from the press of Caxton, the author of the Morte d’Arthur, a late medieval compilation in English, reads ‘sang real’ (holy blood) instead of ‘san greal’ (holy grail). In combination with other evidence, this has led a number of scholars in the wake of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (Baigent-Leigh-Lincoln, 1982) to argue for a symbolic interpretation of the Grail mythology as referring to the hidden bloodlines of the descendants of Christ’s immediate family, known to Eusebius of Caesarea and his followers as the desposyni (Gk. ‘descendants of the master’, a term not denoting direct descent from Christ, but via his extended family).

Although few medievalists have pursued this theory in a scholarly capacity, this hypothesis has gained widespread popularity in pop culture following Dan Brown’s blockbusting Da Vinci Code. However, this interpretation is not the only one which has obsessed occultists.

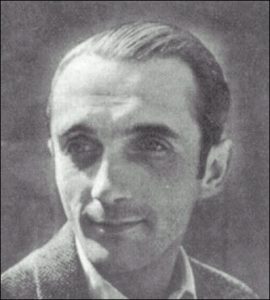

Most notable, in this regard, is the strange legacy of the German intellectual Otto Wilhelm Rahn,

whose academic reputation, like that of Heidegger, never recovered from his personal association with Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. However, if Rahn’s naïve opportunism may be forgiven (in his defence, Rahn committed suicide or was murdered before the atrocities of the Holocaust were committed), his book Kreuzzug gegen den Graal (Crusade against the Grail, 1933) remains a work worthy of detailed study, for the interesting if not always verifiable links it poses between the Grail symbolism and Catharism.

The book, unfortunately for Rahn, gained the admiration of Heinrich Himmler (leader of the Schutzstaffel, originally conceived as Hitler’s bodyguard or Protection Squad and constructed as a pseudo-chivalric organisation concocted as a macabre parody of the Templars) who cooped Rahn inter the Nazi inner sanctum, the research section of the secret society behind the Nazi party, known as the Ahnenerbe. Herein lies the historical background to the Indiana Jones story, as it was Hitler (himself a lifelong fan of Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, a copy of which he personally annotated in detail during his student days, according to Trevor Ravenscroft in The Spear of Destiny [1973]) who authorised the commission to seek the location of true Grail under the direct orders of Heinrich Himmler.

Shortly after Otto Rahn’s death, on 23 October 1940, Himmler visited the Abbey of Montserrat (Spain) carrying with him a copy of Luzifers Hofgesind, eine Reise zu den guten Geistern Europas (1937), Rahn’s sequel to his pioneering study, which already shows signs of the karmic despair which overcame the author.

Himmler believed the grail had been taken to Montserrat after the fall of Montsegur (1244). So convinced of Rahn’s hypothesis was Himmler, that he even threatened the bemused and terrified abbot with the destruction of his holy shrine.

Further details of the exchange between the abbot and Himmler have not been recorded, but it seems that Himmler did not put his threat into practice. And the Nazis, unwilling to further disturb their fascist Spanish allies, never returned to Montserrat.

European pre-Christian cultures believed that nature was divine, and that humanity was part of the natural world and in harmony with the divine other world. So, as long as human consciousness remains blocked in a state of imbalance between nature and the divine, the Grail quest for the once and future king seems set to remain one conduit among many for all the daughters and sons of Adam and Eve to bring healing to the Wasteland.

Griselda Lozano #Òc